George H.W. Bush, the CIA and a Case of State-Sponsored Terrorism

Forty-two years ago, a car-bomb exploded in

Washington killing Chile’s ex-Foreign Minister

Orlando Letelier, an act of state terrorism

that the CIA and its director George H.W.

Bush tried to cover up, Robert Parry reported

By Robert Parry Special to Consortium News

In early fall of 1976, after a Chilean government assassin had killed a Chilean dissident and an American woman with a car bomb in Washington, D.C., George H.W. Bush’s CIA leaked a false report clearing Chile’s military dictatorship and pointing the FBI in the wrong direction.

In early fall of 1976, after a Chilean government assassin had killed a Chilean dissident and an American woman with a car bomb in Washington, D.C., George H.W. Bush’s CIA leaked a false report clearing Chile’s military dictatorship and pointing the FBI in the wrong direction.

The bogus CIA assessment, spread through Newsweek magazine and other U.S. media outlets, was planted despite CIA’s now admitted awareness at the time that Chile was participating in Operation Condor, a cross-border campaign targeting political dissidents, and the CIA’s own suspicions that the Chilean junta was behind the terrorist bombing in Washington.

In a 21-page report to Congress on Sept. 18, 2000, the CIA officially acknowledged for the first time that the mastermind of the terrorist attack, Chilean intelligence chief Manuel Contreras, was a paid asset of the CIA.

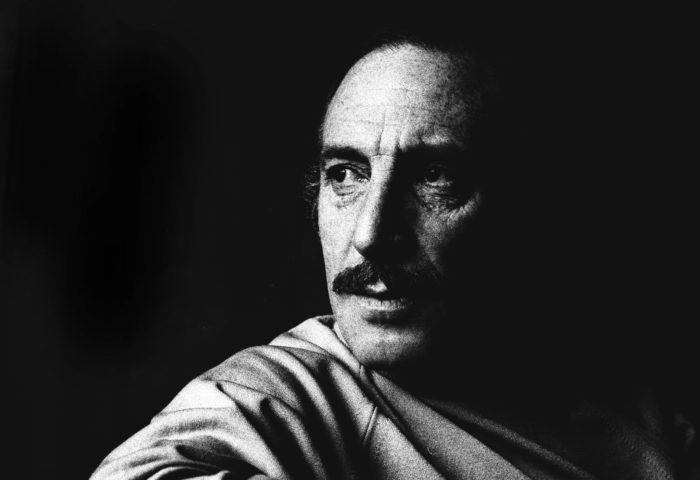

The CIA report was issued almost 24 years to the day after the murders of former Chilean diplomat Orlando Letelier and American co-worker Ronni Moffitt, who died on Sept. 21, 1976, when a remote-controlled bomb ripped apart Letelier’s car as they drove down Massachusetts Avenue, a stately section of Washington known as Embassy Row.

In the report, the CIA also acknowledged publicly for the first time that it consulted Contreras in October 1976 about the Letelier assassination. The report added that the CIA was aware of the alleged Chilean government role in the murders and included that suspicion in an internal cable the same month.

“CIA’s first intelligence report containing this allegation was dated 6 October 1976,” a little more than two weeks after the bombing, the CIA disclosed.

Chilean diplomat Orlando Letelier, murdered when right-wing terrorists blew up his car in Washington on Sept. 21, 1976. (Wikipedia)

Nevertheless, the CIA – then under CIA Director George H.W. Bush – leaked for public consumption an assessment clearing the Chilean government’s feared intelligence service, DINA, which was then run by Contreras.

Relying on the word of Bush’s CIA, Newsweek reported that “the Chilean secret police were not involved” in the Letelier assassination. “The [Central Intelligence] agency reached its decision because the bomb was too crude to be the work of experts and because the murder, coming while Chile’s rulers were wooing U.S. support, could only damage the Santiago regime.” [Newsweek, Oct. 11, 1976]

Bush, who later became the 41st president of the United States (and is the father of the 43rd president), has never explained his role in putting out the false cover story that diverted attention away from the real terrorists. Nor has Bush explained what he knew about the Chilean intelligence operation in the weeks before Letelier and Moffitt were killed.

Dodging Disclosure

As a Newsweek correspondent in 1988, a dozen years after the Letelier bombing, when the elder Bush was running for president, I prepared a detailed story about Bush’s handling of the Letelier case.

The draft story included the first account from U.S. intelligence sources that Contreras was a CIA asset in the mid-1970s. I also learned that the CIA had consulted Contreras about the Letelier assassination, information that the CIA then would not confirm.

The sources told me that the CIA sent its Santiago station chief, Wiley Gilstrap, to talk with Contreras after the bombing. Gilstrap then cabled back to CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia, Contreras’s assurances that the Chilean government was not involved. Contreras told Gilstrap that the most likely killers were communists who wanted to make a martyr out of Letelier.

My story draft also described how Bush’s CIA had been forewarned in 1976 about DINA’s secret plans to send agents, including the assassin Michael Townley, into the United States on false passports.

Then-Vice President George H.W. Bush in a meeting at the White House on Feb. 12, 1981. (Reagan Library)

Upon learning of this strange mission, the U.S. ambassador to Paraguay, George Landau, cabled Bush about Chile’s claim that Townley and another agent were traveling to CIA headquarters for a meeting with Bush’s deputy, Vernon Walters. Landau also forwarded copies of the false passports to the CIA.

Walters cabled back that he was unaware of any scheduled appointment with these Chilean agents. Landau immediately canceled the visas, but Townley simply altered his plans and continued on his way to the United States. After arriving, he enlisted some right-wing Cuban-Americans in the Letelier plot and went to Washington to plant the bomb under Letelier’s car.

The CIA has never explained what action it took, if any, after receiving Landau’s warning. A natural follow-up would have been to contact DINA and ask what was afoot or whether a message about the trip had been misdirected. The CIA report in 2000 made no mention of these aspects of the case.

After the assassination, Bush promised the CIA’s full cooperation in tracking down the Letelier-Moffitt killers. But instead the CIA took contrary actions, such as planting the false exoneration and withholding evidence that would have implicated the Chilean junta.

“Nothing the agency gave us helped us to break this case,” said federal prosecutor Eugene Propper in a 1988 interview for the story I was drafting for Newsweek. The CIA never volunteered Ambassador Landau’s cable about the suspicious DINA mission nor copies of the fake passports that included a photo of Townley, the chief assassin. Nor did Bush’s CIA divulge its knowledge of the existence of Operation Condor.

FBI agents in Washington and Latin America broke the case two years later. They discovered Operation Condor on their own and tracked the assassination back to Townley and his accomplices in the United States.

In 1988, as then-Vice President Bush was citing his CIA work as an important part of his government experience, I submitted questions to him asking about his actions in the days before and after the Letelier bombing. Bush’s chief of staff, Craig Fuller, wrote back, saying Bush “will have no comment on the specific issues raised in your letter.”

As it turned out, the Bush campaign had little to fear from my discoveries. When I submitted my story draft – with its exclusive account of Contreras’s role as a CIA asset – Newsweek’s editors refused to run the story. Washington bureau chief Evan Thomas told me that Editor Maynard Parker even had accused me of being “out to get Bush.”

The CIA’s Admission

Twenty-four years after the Letelier assassination and 12 years after Newsweek killed the first account of the Contreras-CIA relationship, the CIA admitted that it had paid Contreras as an intelligence asset and consulted with him about the Letelier assassination.

Still, in the sketchy report in 2000, the spy agency sought to portray itself as more victim than accomplice. According to the report, the CIA was internally critical of Contreras’s human rights abuses and skeptical about his credibility. The CIA said its skepticism predates the spy agency’s contact with him about the Letelier-Moffitt murders.

“The relationship, while correct, was not cordial and smooth, particularly as evidence of Contreras’ role in human rights abuses emerged,” the CIA reported. “In December 1974, the CIA concluded that Contreras was not going to improve his human rights performance. …

“By April 1975, intelligence reporting showed that Contreras was the principal obstacle to a reasonable human rights policy within the Junta, but an interagency committee [within the Ford administration] directed the CIA to continue its relationship with Contreras.”

The CIA report added that “a one-time payment was given to Contreras” in 1975, a time frame when the CIA was first hearing about Operation Condor, a cross-border program run by South America’s military dictatorships to hunt down dissidents living in other countries.

“CIA sought from Contreras information regarding evidence that emerged in 1975 of a formal Southern Cone cooperative intelligence effort – ‘Operation Condor’ – building on informal cooperation in tracking and, in at least a few cases, killing political opponents. By October 1976, there was sufficient information that the CIA decided to approach Contreras on the matter. Contreras confirmed Condor’s existence as an intelligence-sharing network but denied that it had a role in extra-judicial killings.”

Also, in October 1976, the CIA said it “worked out” how it would assist the FBI in its investigation of the Letelier assassination, which had occurred the previous month. The spy agency’s report offered no details of what it did, however. The report added only that Contreras was already a murder suspect by fall 1976.

“At that time, Contreras’ possible role in the Letelier assassination became an issue,” the CIA’s report said. “By the end of 1976, contacts with Contreras were very infrequent.”

Even though the CIA came to recognize the likelihood that DINA was behind the Letelier assassination, there never was any indication that Bush’s CIA sought to correct the false impression created by its leaks to the news media asserting DINA’s innocence.

Then-Vice President George H.W. Bush with CIA Director William Casey at the White House on Feb. 11, 1981. (Reagan Library)

After Bush left the CIA with Jimmy Carter’s inauguration in 1977, the spy agency distanced itself from Contreras, the new report said. “During 1977, CIA met with Contreras about half a dozen times; three of those contacts were to request information on the Letelier assassination,” the CIA report said.

“On 3 November 1977, Contreras was transferred to a function unrelated to intelligence so the CIA severed all contact with him,” the report added. “After a short struggle to retain power, Contreras resigned from the Army in 1978. In the interim, CIA gathered specific, detailed intelligence reporting concerning Contreras’ involvement in ordering the Letelier assassination.”

Remaining Mysteries

Though the CIA report in 2000 contained the first official admission of a relationship with Contreras, it shed no light on the actions of Bush and his deputy, Walters, in the days before and after the Letelier assassination. It also offered no explanation why Bush’s CIA planted false information in the American press clearing Chile’s military dictatorship.

While providing the 21-page summary on its relationship with Chile’s military dictatorship, the CIA refused to release documents from a quarter century earlier on the grounds that the disclosures might jeopardize the CIA’s “sources and methods.” The refusal came in the face of President Bill Clinton’s specific order to release as much information as possible.

Perhaps the CIA was playing for time. With CIA headquarters officially named the George Bush Center for Intelligence and with veterans of the Reagan-Bush years still dominating the CIA’s hierarchy, the spy agency might have hoped that the election of Texas Gov. George W. Bush would free it from demands to open up records to the American people.

For his part, former President George H.W. Bush declared his intent to take a more active role in campaigning for his son’s election. In Florida on Sept. 22, 2000, Bush said he was “absolutely convinced” that if his son is elected president, “we will restore the respect, honor and decency that the White House deserves.”

The late investigative reporter Robert Parry, the founding editor of Consortium News, broke many of the Iran-Contra stories for The Associated Press and Newsweek in the 1980s. His last book, America’s Stolen Narrative, can be obtained in print here or as an e-book (from Amazon and barnesandnoble.com).

If you value this original article, please consider making a donation to Consortium News so we can bring you more stories like this one.

Please visit our Facebook page where you can join the conversation by commenting on our articles to help defeat Facebook censorship. While you are there please like and follow us, and share this piece!

https://consortiumnews.com/2018/12/01/george-h-w-bush-the-cia-and-a-case-of-state-sponsored-terrorism/?fbclid=IwAR3wM1SHWBFQc74C8FmImKeNRUF2HSSzaddfnnJ-x6biUL1rRUpB4ftO45s

Comments

Post a Comment