|

The Dangerous Austerity Politics of the Washington Post

view post on FAIR.org

The Washington Post (7/17/19) ran a column this month by Maya MacGuineas, the president of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, one of the many pro-austerity organizations that received generous funding from the late Peter Peterson. The immediate target of the column was the standoff over the debt ceiling, but the usual complaints about debt and deficits were right up front in the first two paragraphs:

At the same time, the federal debt as a share of the economy is the highest it has ever been other than just after World War II….

So our plan is to borrow a jaw-dropping roughly $900 billion in each of those years—much of it from foreign countries—without a strategy or even an acknowledgment of the choices being made because no one wants to be held accountable.

This passes for wisdom at the Washington Post, but it is actually dangerously wrong-headed thinking that rich people (like the owner of the Washington Post) use their power to endlessly barrage the public with.

The basic story of the 12 years since the collapse of the housing bubble is that the US economy has suffered from a lack of demand. We need actors in the economy to spend more money. The lack of spending over this period has cost us trillions of dollars in lost output.

This should not be just an abstraction. Millions of people who wanted jobs in the decade from 2008 to 2018 did not have them because the Washington Post and its clique of “responsible” budget types joined in calls for austerity. This meant millions of families took a whack to their income, throwing some into poverty, leading many to lose houses, and some to become homeless.

At this point, the evidence from the harm from austerity in the United States (it’s worse in Europe) is overwhelming, but just like Pravda in the days of the Soviet Union, we never see the Washington Post, or most other major news outlets, acknowledge the horrible cost of unnecessary austerity. We just get more of the same, as though the paper is hoping its readers will simply ignore the damage done by austerity.

And it is not just an occasion column from a Peter Peterson–funded group; the Post’s regular economic columnist, Robert Samuelson, routinely complains about budget deficits, as do the Post editorial writers. We get the same story in the news section as well; for example, a piece this month (7/19/19) told us about the need to “fix” the budget. The Post is effectively implying that a lower budget deficit, which results in lower output and higher unemployment, is “fixed.”

If the Post cared about the logic of its argument, instead of just repeating platitudes about the evils of budget deficits, it should quickly recognize that its push for austerity makes no economic sense. The argument for the evils of a budget deficit is that it is supposed to lead to high interest rates and crowd out investment. That leaves the economy poorer in the future, since less investment leads to less productivity growth, so the economy will be able to produce fewer goods and services in future years. (The implicit assumption is that the economy is near its full-employment level of output, so that efforts by the Fed to keep interest rates down by printing money would lead to inflation.)

The nice part of this story is that there is a clear prediction which we can examine: High budget deficits lead to high interest rates. Or, if the Fed is asleep on the job, high budget deficits will lead to high inflation.

The interest rate on 10-year Treasury bonds at the end of last week was just over 2.0 percent. That is incredibly low by historic standards, and far lower than the rates of over 5.0 percent that we saw when the government was running a surplus in the late 1990s. The inflation rate is hovering near 2.0 percent, and has actually been trending slightly downward in recent months. So where is the bad story of the budget deficit?

In the classic deficit-crowding-out-investment story, if we cut the budget deficit, investment rises to replace any lost demand associated with lower government spending or higher taxes. We can also see some increased consumption, mostly due to mortgage refinancing, and some increase in net exports due to a lower-valued dollar.

But what area of spending does the Washington Post and its gang of deficit hawks think will fill the gap if it could find politicians willing to carry through the austerity it continually demands? It shouldn’t be too much to ask a newspaper that endlessly harps on the need for lower deficits to have a remotely coherent story on how lower deficits could help the economy.

There is also the burden-on-our-children story that the Peter Peterson gang and the Post likes to harangue readers with: Our children will inherit this horrible $20 trillion debt that they will have to pay off over their lifetimes.

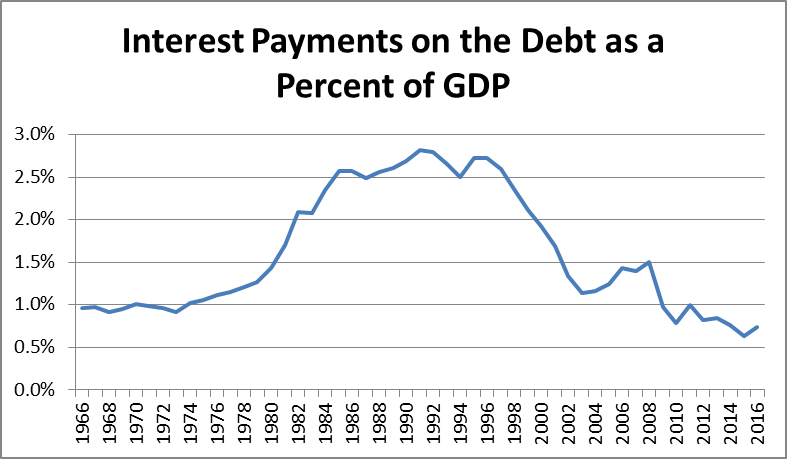

Net interest rebated to the Treasury by the Fed (CEPR, 1/18/17)

This story makes even less sense than the crowding-out story. The burden of the debt is measured by the interest paid to bondholders, which is actually at a historically low level relative to GDP. It’s around 1.5 percent, after we subtract the interest rebated by the Fed to the Treasury. It had been over 3.0 percent of GDP in the early and mid-1990s.

And even this is not a generational burden. It is a payment within generations from taxpayers as a whole to the people who own bonds, who are disproportionately wealthy. Much of this money is recaptured with progressive income taxes. More could be captured with more progressive taxes.

But this is actually the less important issue with this sort of accounting. Direct government spending is only one way the government pays for things. It also provides patent and copyright monopolies to provide incentives for innovation and creative work. These are alternatives to direct government payments.

To be specific, if the government wants Pfizer to do research developing new drugs, it can pay the company $5–10 billion a year to do research developing new drugs. Alternatively, it can tell Pfizer that it will give it a patent monopoly on the drugs its develops, and arrest anyone who tries to compete with it.

Generally, the government takes the latter route with innovation. This can lead to a situation where Pfizer is charging prices that are tens of billions of dollars above the free market price. This monopoly price is equivalent to a privately imposed tax that the government has authorized the company to collect.

Anyone seriously interested in calculating the future burdens created by the government would have to include the rents from patent and copyright monopolies, which run into the hundreds of billions of dollars annually, and possibly more than $1 trillion. (They are close to $400 billion with prescription drugs alone.) The fact that the deficit hawks never mention the cost of patent and copyright monopolies shows their lack of seriousness. They are pushing propaganda, not serious analysis.

I got a taste of this propaganda effort firsthand earlier this year, when I was asked by an editor at the Washington Post to write a piece on Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). While I’m largely sympathetic to MMT (it’s essentially Keynesianism—that’s not an insult; the name is taken from a phrase in the Treatise on Money), I have some differences. In particular, I am not willing to give up having the Fed as a check on inflation.

I also think the proposal for a job guarantee is a very big lift. It is a good idea in principle, but one that must be moved towards gradually with smaller programs, like the one recently proposed by Sen. Chris Van Hollen. Jumping to a program that could add 20 to 30 million people to the government payroll strikes me as a recipe for disaster.

There are also Twitter MMTers who view it as meaning the government can spend whatever it wants on things like Green New Deal or Medicare for All. This is not a view that the leading promulgaters of MMT hold, but for some, this is what the theory means.

Anyhow, I was happy to make these points in a column in the Post, as I have done elsewhere. I went through a couple of rounds of edits, with the editor both times making the piece more critical. I decided to throw in the towel after round two. The editor wanted me to include a needlessly snide remark from a MMT critic, and had me referring to the theory as “dangerous.”

That comment left little doubt that they wanted a different column than the one I had written. MMT is dangerous? How much output has the austerity pushed by the Post’s regular contingent of commentators and reporters cost the country? More importantly, how many lives have been ruined by needless unemployment, and the resulting loss of income and poverty?

Seeing the needless hardship the country has endured because of austerity since the Great Recession, it really takes some nerve to refer to MMT as “dangerous.”

Anyhow, I suspect the Post’s editors are immune to criticism. Just like the millions who mindlessly pledge allegiance to Donald Trump, they will push the austerity line they have always pushed, regardless of the evidence.

But it is important to call out the Post’s austerity nonsense for what it is. This is not serious economics; it is a doctrine that imposes pain, with the only gain going to those who will get cheap help as a result of higher unemployment.

A version of this post originally appeared on CEPR’s blog Beat the Press (7/25/19).

Messages can be sent to the Washington Post at letters@washpost.com, or via Twitter@washingtonpost. Please remember that respectful communication is the most effective. Feel free to leave a copy of your message in the comments thread of this post.

|

|

Comments

Post a Comment