|

‘We Should Expect Them to Keep Developing New Ways to Subvert Public Will’ - CounterSpin interview with Paul Rosenberg on GOP power grabs

view post on FAIR.org

Janine Jackson interviewed Paul Rosenberg about Republican post-election power grabs for the December 14, 2018, episode of CounterSpin. This is a lightly edited transcript.

MP3 Link

Janine Jackson: One can make too much of political gestures. But when 44 former senators co-sign an op-ed declaring that the country is “entering a dangerous period,” there may be something to see here. The piece, signed by 32 Democrats, ten Republicans and two independents, had reference to investigations of Donald Trump. But the ex-lawmakers’ stated concern about “the rule of law and the ability of our institutions to function freely and independently” could be well-applied in numerous places around the country. Where, as our next guest reports, we are seeing in the wake of the midterms, “a red tide of anti-democratic power grabs—strategies, tactics and rationales designed to deny the will of the voters.”

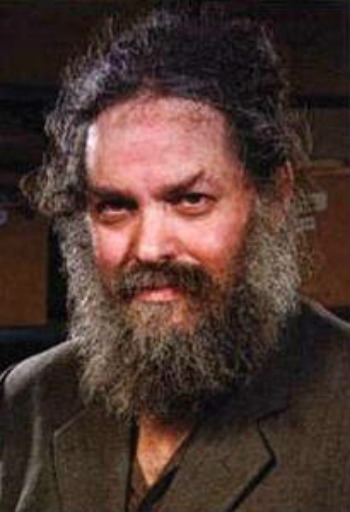

Paul Rosenberg is a writer and activist. He’s senior editor for Random Lengths News, as well as a columnist for Al Jazeera English and a contributor at Salon.com. He joins us now by phone from Southern California. Welcome back to CounterSpin, Paul Rosenberg.

Paul Rosenberg: Thank you.

JJ: There’s a lot of skullduggery to talk about. I know in your recent piece for Salon, you break it into some different categories, but really, start anywhere you like on these power grabs that are going on.

PR: I think the most blatant, that has gotten the most attention, have been in Wisconsin and secondarily in Michigan, where you just have this wholesale rebellion of the legislatures against the will of the people. And in Wisconsin, you had a Democrat elected governor and attorney general, and you have the legislatures try to take power away from them, or succeed, so far. There may be court battles that will probably drag out. This is what’s expected.

Similarly, same thing in Michigan. Although there you have three women elected to the governor’s, the attorney general and the secretary of state positions. And all three of them are under attack there. Plus a whole raft of three citizen initiatives that they’re trying to cripple, and then two other initiatives that were taken off the ballot, because they were passed by the legislature instead, and that then enabled them to come back and fiddle with them afterwards.

And this was something that’s never been done before. But, in fact, there was an opinion by the attorney general, dating back to 1964, I believe, that said you couldn’t do that. But then after the midterm elections, the defeated candidate for governor, who’s the sitting attorney general, wrote a new opinion that said, “Yes, I can do that.”

Paul Rosenberg: “Basically based on gerrymandered districts, these permanent majorities that do not have majority support are taking power away from the people and from their elected representatives.”

And so you’re seeing all this, basically based on gerrymandered districts, these permanent majorities that do not have majority support are taking power away from the people and from their elected representatives, the governors, attorney general and, in the case of Michigan, also the secretary of state.

So that’s sort of the essence of what the most consistent pattern has been, and we see that also in several other places. The Florida people were very aware of the restoration of felon voting rights. Well, after that happened, there’s been a similar thing happening in Florida, where the chief election officer is saying, “Well, I need some guidance in terms of how this should be implemented.” And the people who passed it said, “No, you don’t need any guidance at all. It’s completely self-executing.” And so there’s talk there about the legislature getting involved with that as well.

JJ: I just want to draw you out—in case that’s not clear for folks—we’re talking about ballot initiatives. And in Michigan, you say it was “pulled off the ballot,” and that was in order to make it something that the legislature could then go back in and fiddle with. And “fiddle with,” we can understand that to mean as much as overturn the intention of the original initiative.

PR: Well, basically to really subvert it. There were two of them. One was for a minimum wage increase, and the other was a paid leave act. And what they did was significantly weaken them. The figures on the minimum wage law is it was going to go to $12 an hour by 2022, and by 2024 for tipped workers. And they changed it so it would only go to $12 an hour by 2030; that’s quite a bit longer. They eliminated the cost of living adjustments as well.

And for the tipped workers, it would only go up to $4.58 per hour, with the employers responsible for making up the difference if they fell below that. But that’s a very much more muddled situation, and it was, again, by 2030. So we’re talking about a much longer period of time. And, given inflation, it’s not even clear that that’s really going to be any increase at all.

JJ: And the point is, it’s not what people said they wanted.

PR: It was nothing close to what they said. But it’s a combination of subverting the will and making it so confused, it’s even hard to understand what’s going on. So it’s both confusing and subverting.

JJ: In your piece that’s up at Salon, you walk through a lot of this information, and a question that comes to the reader’s mind, and that you respond to, is, “Is this legal?” You know? And it turns out that a number of these moves, they’re legal, but people don’t do them.

PR: Right. The phrase “constitutional hardball” was introduced by law professor Mark Tushnet when he was at Georgetown, I guess it was in 2003 or so; he’s now at Harvard Law. And he means, basically, something that is technically legal under the Constitution, but that people just haven’t done.

And it was conceived of at the federal level, but it’s applicable here as well, and it’s even more complicated, because what may be constitutional under state constitution and the federal Constitution may be at variance, and so it can get very tangled up.

And in some cases, some of these things may be illegal. They’re just so over the line. But the idea, basically, is to do things you can get away with, that will be found legal, but that no one would ever have thought of doing.

And, you know, it is legal for an attorney general to overturn a previous opinion of another attorney general. There’s no law against doing that. It just isn’t done, especially done after the election, so that then they can act in a lame duck session. That violates several norms at once.

JJ: Absolutely, absolutely.

PR: But it’s not illegal. At least not on its face. Now, of course, it could be illegal. It could go up to the state supreme court, and the state supreme court might say, “Uh-uh. You can’t do that. It violates a key fundamental constitutional principle.” Being as those principles are upheld by norms, and it’s only if a court rules that that norm has the force of law, that it then becomes illegal.

And so that’s what hardball is all about. It’s about reshaping the norms. It’s something that conservatives do a lot more than liberals, because they’re interested in really changing the way our government works. They’re really in a long-term effort to undo the New Deal, and all of the state constitutions that have similar kinds of governing philosophies.

JJ: At various points in this article, you note undercoverage, and I’m hearing you say how thorny it is, and at the same time, it’s not impossible to see through it. It’s not impossible to make sense of what’s going on. So any undercoverage is lamentable, especially given that darkness is only going to abet these kinds of anti-democratic measures.

PR: Clearly. And they do things very, very quickly, precisely because of that, because they don’t want people looking and seeing what they’re doing. When people did get wind–I mean, we had another wave of incredible protests in Madison, Wisconsin, reminiscent of 2011, precisely because of that, because they were trying to rush something through so quickly, because they were hiding it as best they could.

JJ: And then, just before I got on the phone to talk to you, I was looking through coverage, and I saw a factchecking piece from the Associated Press, and of course with reference to Evers and Walker in Wisconsin. And the headline was, “Will Evers Still Have Plenty of Power?” You know?

And I just thought, “Wow, is that the angle we’re going to go for?” Like, “Oh, it doesn’t matter. He’s still gonna have plenty of power.” What would be useful journalism at this point?

PR: I think the more useful journalism is to talk about it, quite frankly, in terms of growing authoritarianism, because this is what they’re trying to do. They are trying to take power away from the people, away from their elected representatives.

Another aspect of this, which I didn’t get into in this story, because this is about these particular sets of actions, but I did reference it. There are similar kinds of actions in stripping power and restricting state courts.

JJ: Right.

PR: But it’s precisely because state courts can say, “No, you can’t do this,” and legislators don’t want courts telling them what they can do. So they’ve been stripping power of state courts as well.

And that’s basically all the kinds of things that, as you said in your introduction, people are waking up to with Donald Trump.

But Trump didn’t invent this. Trump is just the worst symptom of something that’s going on for a very long time. And the whole thrust of it is basically a move in the direction of an authoritarian regime. And it should be seen in the same terms as what we see happening around the world, from the Philippines to Turkey to the [former] Soviet Union, all these other places that we justifiably could point our fingers at in horror; we’re going through something very similar ourselves.

JJ: I’ll just say, finally, you do point to pushback that’s ongoing. It’s not that this is happening under complete darkness. The people, when they’ve had it put before them, have indicated that they’re interested in moving to structurally stop this sort of thing.

PR: Right. There were very successful initiatives to implement nonpartisan redistricting commissions. And even in Michigan, where Republican officeholders attacked it as a power grab, it was just overwhelmingly approved. And in North Carolina, where the Republicans tried to cripple the election oversight board, that was rejected overwhelmingly there too.

So the public sentiment is very strongly against this. And, you know, I think that developments like the formation of Indivisible groups, and other similar kinds of groups that have popped up around the country, have been very important in changing the climate, and are going to be even more important going forward, because it’s decentralized resistance like this, that’s not atomized, that’s networked, but that’s also not imposed from the top. Because even the best-intentioned political leaders at the top of parties are compromised by the nature of those parties.

And it takes consistent grassroots pressure from below to really achieve the kind of change that’s needed.

Hopefully we’ve seen a lot more of that this time around. And we’re just going to need an awful lot more of that going forward to continue countering this, because they’re not they’re not going to stop what they’re doing. They’re fighting in ways that people have never expected before, and we should expect them to keep developing new ways of trying to subvert public will.

JJ: We’ve been speaking with Paul Rosenberg. His piece, “GOP’s Anti-Democratic ‘Red Tide’: It’s Ugly, but It’s Nothing New,” can still be found at Salon.com. Paul Rosenberg, thank you so much for joining us this week on CounterSpin.

PR: Well, thank you for having me.

|

|

Comments

Post a Comment